Changing weather, changing lives

A glimpse from around the globe

From Bolivia to Cambodia, the story is the same: Weather patterns are changing.

In these accounts, journey with us to see how people, with bravery and determination, are facing profound shifts in their lands and livelihoods.

We care about climate change because we care about neighbors, here and across the world, all made in God's image.

May we open our hearts to their stories.

Scroll down to read accounts from MCC's work around the world.

What you can do: Explore ideas for how you can make a difference

(Top photo: Dicomedes Quispe Lorenzo is part of an MCC-supported project in Bolivia to help farmers adapt to the changes climate change has brought in remote, mountainous regions. MCC photo/Annalee Giesbrecht)

Bangladesh

Because of changing weather, there are more pests, so we farmers are using more insecticides, which is affecting our health."

Buli Murmu

As one part of the climate changes, problems in other, new areas can suddenly loom large. In Panchbibi, Bangladesh, rising temperatures mean more insects are hatching, threatening the harvests of farmers like Buli Murmu.

The usual response is chemicals; often in Bangladesh farmers will use higher doses of commercial pesticides and fertilizers. But Murmu is taking a more natural approach.

Through a project of MCC and a Bangladeshi partner, Peoples Union of the Marginalized Development Organization, she and others in her community are turning to vermicomposting — raising worms that help to break down organic material and provide affordable compost. “If we use this compost in the fields, we don’t need pesticides. Our crops will be more nutritious,” she says.

Bolivia

"Before we didn’t have hail. We’re struggling with hail, it’s costly for our people and our crops."

Teofilo Colque

In remote, mountainous communities in Bolivia, farmers like Teofilo Colque feel the effects of climate change most keenly in how unpredictable and extreme the weather has become. High-altitude areas that were too cold to grow a variety of crops have warmed, expanding what people can harvest. But the threat of killing frosts and devastating hail has grown as well.

In response, MCC partners are working with Colque and others to help them find new ways to use irrigation and soil conservation techniques to grow more diverse crops, even in difficult land. “This used to be only rocks, but with the knowledge I’ve acquired, I’ve turned it into a garden,” Colque says. “Before this, nothing grew, but we’ve turned rocky land into cultivable land.”

Burundi

As weather patterns have fluctuated, farmers like 60-year-old Nahimana Marceline in Makamba province, Burundi, are facing more extended dry periods. "The rain delays and it is not sufficient," she says. Then, when it comes, it may be a deluge that destroys the crops.

In response, MCC partner Help Channel Burundi is offering farmers new techniques to increase production and deal with the impact of climate change. For example, "Now we mulch our farms. With this technique, we save water, and It does not run away. When we mulch, we keep moisture in the field. Even if the rain were little, mulching kept the soil humid. Later on, those grasses used for mulching will become manure to feed the soil." She also uses contour lines in her land to fight against erosion and encourage water to seep slowly into the ground and feed the crops.

"I had a fear of not having enough food," she says. "But since now I am learning new techniques, there’s hope. Even (though) I am getting old, I will pass on the knowledge learned here to my offspring and then continue the chain of development."

"Today’s weather patterns affect my community and neighbors. Let me tell you, if people do not have enough food, the generosity disappears. We’re all hungry when we don’t harvest due to the climate change."

Nahimana Marceline

Cambodia

Back then, all of the farmers, and my family too, grew rice irrigated only by the seasonal rains."

Chhin Ya

In Cambodia’s Prey Veng Province, Chhin Ya stands in the rice field that was sufficient to provide food and a livelihood for her and her parents when she was young. But droughts have ruined harvests and reduced yields. As crops failed, the family borrowed money for food. Their debt grew. Her daughter dropped out of school and migrated to work in a garment factory. Her husband also left the district to find work.

Through MCC partner Organization to Develop Our Villages (ODOV), though, she was able to establish a fishpond and a garden she can water from the pond. Although the region struggles with ponds, lakes and canals that often dry up, her food security and earnings have improved — enough that her husband stopped migrating for work and now helps her raise fish and vegetables. she says.

Canada

I never knew of a time where food would be scarce. There were rabbits, sharp-tailed grouse, spruce grouse, ptarmigans, caribou, moose. Everything you needed to eat was outside the door."

Bill Louttit

By the time he was 5, Bill Louttit (at right in photo) was on his way to a lifetime of hunting wild game to feed his family and community. That was the norm for the fly-in community of Lake River, on the western shores of James Bay, as it was for many other Indigenous communities in northern Ontario.

Today, though, fewer and fewer Indigenous communities can rely on wild game for sustenance — in part due to climate change and its effects on habitats and wildlife patterns. "We used to catch trout, and then it was pike, and now we have some fish that we haven’t seen before. There’s no name for it in Cree,” Louttit says. Also, the opportunity to learn skills like hunting was disrupted for many Indigenous people by residential schools and government policies restricting access to land.

Without traditional food systems and knowledge, most Indigenous communities rely on over-priced food shipped from urban centers. The price of fresh produce and meat in northern Ontario communities is triple that of urban areas in southern Ontario.

In response, MCC has partnered with First Nations communities all over northern Ontario to support food sovereignty with initiatives like community garden kits which come complete with all the tools and seeds needed to start a large garden. MCC also advocates alongside Indigenous partners for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission calls to action, which include addressing the need for Indigenous food sovereignty.

Haiti

"We don't have rain."

Saintanise Fleurinord

In Kabay, a community in the Artibonite mountains in Haiti, the change in rainfall patterns has been striking. Often, even if there is rain in the valley, there is no rain in the mountains and on people's fields and gardens.

"We know nowadays there is not enough rain for farmers to find enough water and the means to produce enough food to eat. This has caused life to become difficult," says Jean-Remy Azor, executive director of MCC partner Konbit Peyizan.

In response, MCC partner Konbit Peyizan trains farmers in Kabay in conservation agriculture and works with the community to help them produce fruit and vegetables despite the challenges.

There are successes: Saintanise Fleurinord has a garden with a large mango tree and many plantain trees. Yet, even after trainings and tools, one thing remains consistent for Fleurinord and other farmers: There is still not enough rain.

Honduras

"The roof, the walls, the floor, furniture were all ruined. … We had to throw everything away."

Amadeo Castillo

After Hurricanes Eta and Iota stormed through Central America within two weeks in November 2020, Amadeo Castillo and his family returned to their home in Choloma, Honduras, to find a half meter (1 1/2 feet) of mud inside.

That year was one of the most active hurricane seasons on record, with Iota being the strongest hurricane so late in the season, says Bruce Guenther, MCC’s director of disaster response. “As in other regions of the world, we are seeing the impacts of climate change play out, impacting millions of vulnerable people.”

By November 2021, thanks to materials from MCC and the Comisión de Acción Social Menonita (CASM), a development organization born out of the Evangelical Mennonite Church of Honduras, Castillo and his family stand outside their repaired home, complete with a new zinc roof that keeps them dry.

“That is a gift sent by God,” says Castillo, shown with his wife Suyapa Arely Rivera Villanueva and their three children Maria, 8, Fernanda, 4, and Ana, 1. “We feel really happy because we are living more calmly, with more confidence and asking God that there not be another disaster right now.”

India

"There was always a fixed rainfall pattern, but in the last 10 years it's changing though, and that's a big challenge. And the amount of rain is also reducing."

Santosh Birhor

India is home to some 100 million migrant workers, nearly half of them working on large irrigated farms.

But once they are back in their rural home villages, farmers like Santosh Birhor must depend on India's rainy monsoon season if they want any chance of supporting themselves with small-scale farming.

And now, climate change is causing the monsoon season to shift and become less consistent, putting the livelihoods of tens of millions of people at risk.

In India, MCC partners including CASA (Church's Auxiliary for Social Action) are responding. Through their efforts, farmers like Birhor benefit from training in how to better plant and care for their crops and in using techniques like natural pesticides and crop rotation. The improvements give Birhor and others more tools to adapt to the changes in climate they're encountering, and more of a choice to earn a living by farming at home rather than migrating for work.

Jordan

"It breaks my heart to see my hometown turn dry, ugly and dusty. But the Green School project gives my community hope now."

Fatima Al-Sawa’dah

Al-Sawa’dah Secondary Mixed School is in Malih, a frontier of the Eastern Desert region of Jordan, and the land has gotten drier.

Fatima Al-Sawa’dah, environmental club supervisor and school counselor Ola Al-Khodour recall that in the1980s this area was characterized by more rainfall and the bushes and fields that rain helped to grow. People were able to use river water to irrigate crops and gardens.

But since the mid-1990s, the rain has receded. "The region began to turn to drought and lands became barren," Ola says. Today, Malih is dry and dusty, with declining numbers of trees and a lack of water resources. Students have been limited in how much fresh water they can use, and the area itself has a water network that pumps water only once a week for four hours.

But today, thanks to a project of MCC and Madaba for Supporting Development, the school enjoys a steady supply of clean water. A grey water tank captures and stores water that will irrigate a green zone of new trees and plants. Through an environmental club, students take an active role in helping to water the green space and encourage conservation.

Students, parents and even teachers are embracing the changes and becoming more invested in the school. "I stand tall and proud that I serve at the Green School of Sawa’dah. Before I used to shy away," Fatima shares, saying that the Green Schools project "gives my community hope now."

Kenya

"Rain is everything."

Francisca Mbai

At home in Makueni County, Kenya, 56-year-old Francisca Mbai recalls when rain could be counted on to come in March, April and May, and again in October, November and December. Droughts were not unheard of, but were much less common. Harvests were more assured, and rainfed lands provided enough fodder for livestock.

Now, more often than before, “Rain fails, and we harvest nothing,” she says. Often then, men migrate to urban areas for work. Women, she says, are most affected by climate change because they bear the burden of figuring out how to meet the family’s basic needs and pay costs like school fees.

Through MCC partner Utooni Development Organisation, Mbai was trained in conservation agriculture and joined a savings group where she and others pool their money. Participants can take out loans, a source of capital that helps Mbai and others raise animals or start businesses, providing families with a safety net if rains don’t come.

And efforts can add up. Mbai, for instance, used a loan from the savings group to buy chickens to raise as an extra source of income. With earnings from the chickens, she was able to buy a 5,000-liter water tank to harvest rainwater (pictured above). She used other loans for solar lights, higher-quality seeds and more.

Malawi

"Sometimes once, sometimes twice, depending on the availability of food."

Ndiuzani Butao

— taking with them Ndiuzani Butao’s plans for a better harvest.

As a lead farmer in an MCC-supported project, 22-year-old Butao was embracing new lessons in conservation agriculture, hoping they would provide more food for her elderly grandmother, her 1-year-old daughter Hanna Danela and her teenage brother.

It was one way that she and her family could work to withstand the more erratic rainfall and frequent flooding that climate change has brought to this region of Malawi.

Instead of harvesting, though, she’s grappling with the aftermath of a cyclone that took all but one dwelling on her homestead, forcing her brother to move in with a friend. It destroyed clothes, bedding, schoolbooks and kitchen utensils — as well as stored food and chickens.

A field where the family had planted cotton, maize, sorghum, millet and cowpeas was washed away. Pests came to the region, nibbling what crops remained. Her family was worried that if flooding continues, they may have to move to another area.

Butao’s challenge was more immediate.

How could she, as the breadwinner, earn enough to feed her daughter and her grandmother?

In the weeks after the storm, she worked for others and was paid mostly in flour. Asked how many times the family had meals per day, she answered: “Sometimes once, sometimes twice, depending on the availability of food.”

MCC is providing food assistance to 500 of the most-affected families in the region for two months, helping to nourish families for today — but unable to control what the weather may bring later this year or next.

Nepal

"In March/April, when less water is available, the queue to the well was very long ... we would keep our children in the queue early in the morning or at night waiting for our turn to come."

Beli Chepang

In mountainous regions of Nepal, the problem of water sources drying out has become more common in recent years due to climate change, shares Durga Sunchiuri, program coordinator for MCC Nepal. When rain is sparse for months after the monsoon season, water recharge systems weaken, and sources dry up. As thousands of families face difficulties having enough water for agriculture and even to drink, many are migrating to other areas. He notes that a recent census report from 2021 shows that the population has significantly decreased in the mountainous regions of Nepal and increased in the southern plain.

In villages like Thansingh in Nepal’s Dhading district, lines grew at the community well, even at night, leaving mothers like Beli Chepang spending more time in line. Sometimes, Chepang had to walk with her youngest child on her back, to fetch water further away. She couldn’t maintain a kitchen garden in the winter and dry season as there was no water.

But through MCC partner Shanti Nepal, the village was able to work together to build a reservoir and install a water tap in each home. More water means better hygiene for the family and more time to care for children and maintain a kitchen garden, Chepang says.

Rwanda

"No sooner had I planted than rains disappeared. This season, we hardly produced any crops, and the price of

maize has doubled ..."

Pascal Nizeyimana

When Pascal Nizeyimana was growing up in Rwanda’s Bugesera district, the rains began in September, and farmers immediately planted cassava, sweet potatoes, bananas and other crops. Harvesting was in January. Farming today is much more challenging, he says. “We have to apply fertilizer and pray that we get rain. For example, the peanuts I planted in October ultimately failed. It’s February, and they didn’t produce anything.” Instead of growing all the food for the family and food to sell, his family now must buy all their food. “In turn, this has led to us reducing the food portions for the household members, and sometimes we adults don’t have lunch so our children can have enough food.”

Lessons from MCC partner Peace and Development Network in conservation agriculture have helped him reduce soil erosion, retain moisture and improve soils, and he has received support through Friends Peace House, another MCC partner, to get livestock and irrigation equipment to grow crops in the dry season.

Yet, he says, “With every season getting more unpredictable than the one before, I am worried that we may be more food insecure in the future.”

Uganda

"There is hunger. There are diseases. Cattle

rustling increases. When there is rain, all

these things reduce."

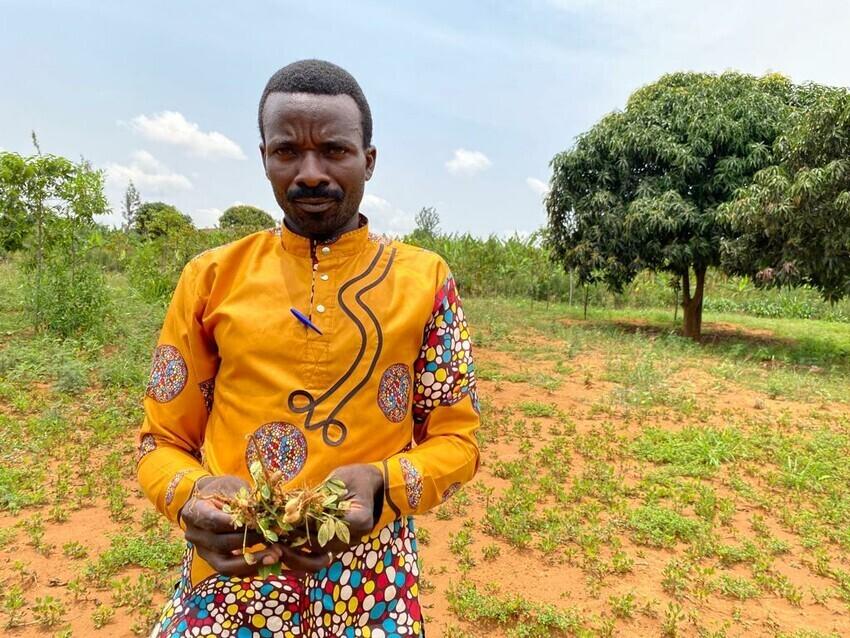

Samson Dekeny

In a remote community in Karenga District, Uganda, Samson Dekeny points out the remains of his sweet potato plants, their leaves yellow from drought, the insides eaten by pests. “This is mainly a crop we use to sell. We use the money for school fees, medical bills and emergencies at home.”

If rains do come, but weeks later than expected, “People suffer because the yields they get during that time do not support them up to the next growing season,” he says.

Through MCC partner Dynamic Agro-pastoralists Development Organization (DADO), Dekeny is using conservation agriculture to help his crops withstand drier weather. He also uses intercropping, planting various crops side by side throughout the year, so if one fails to produce, others may succeed.

And he is working to protect the environment. “I planted 50 trees, mostly teak trees. As you can see, I put my mango right here. They are mostly for my family. This is just because I have this in mind, that trees are very OK,” he says. Long-term he hopes that planting trees will create a healthier environment, leading to more rain that will support crops like his sweet potatoes.

Zambia

"These are the remains of the gardens. These are the remains of the plants in the gardens that were completely stripped out by the floods."

Hangala Bornface

Hangala Bornface, an environmental protection officer of MCC partner Choma Child Development of Zambia’s Brethren in Christ Church, stands in an area of Zambia’s Southern Province where the usual danger is drought.

Indeed, early in 2022, the rains were delayed. But then, the dry land was inundated with sudden, strong flooding – washing away banana plants, fruit trees and other crops. “This is posing a serious threat of hunger and food shortages in this community,” he says.