Palestinian needlework and MCC

A traditional art form gives Palestinian women uprooted by war a chance to earn new income.

The MCC-sponsored Palestinian needlework program was established in 1952 to provide income to refugee families who had been displaced from their homes during the 1948 war. At its height in the 1960s, more than 1,000 women from the Jericho and Hebron areas were involved. The program was transferred to the village women of Surif in 1979 and continues to operate as a self-sustaining cooperative. Heather Lehman, who was a representative for MCC’s work in Palestine and Israel with her husband Ryan from 2007 to 2010, reflects on this embroidery tradition and the hope the MCC needlework program brought to women in times of war and displacement.

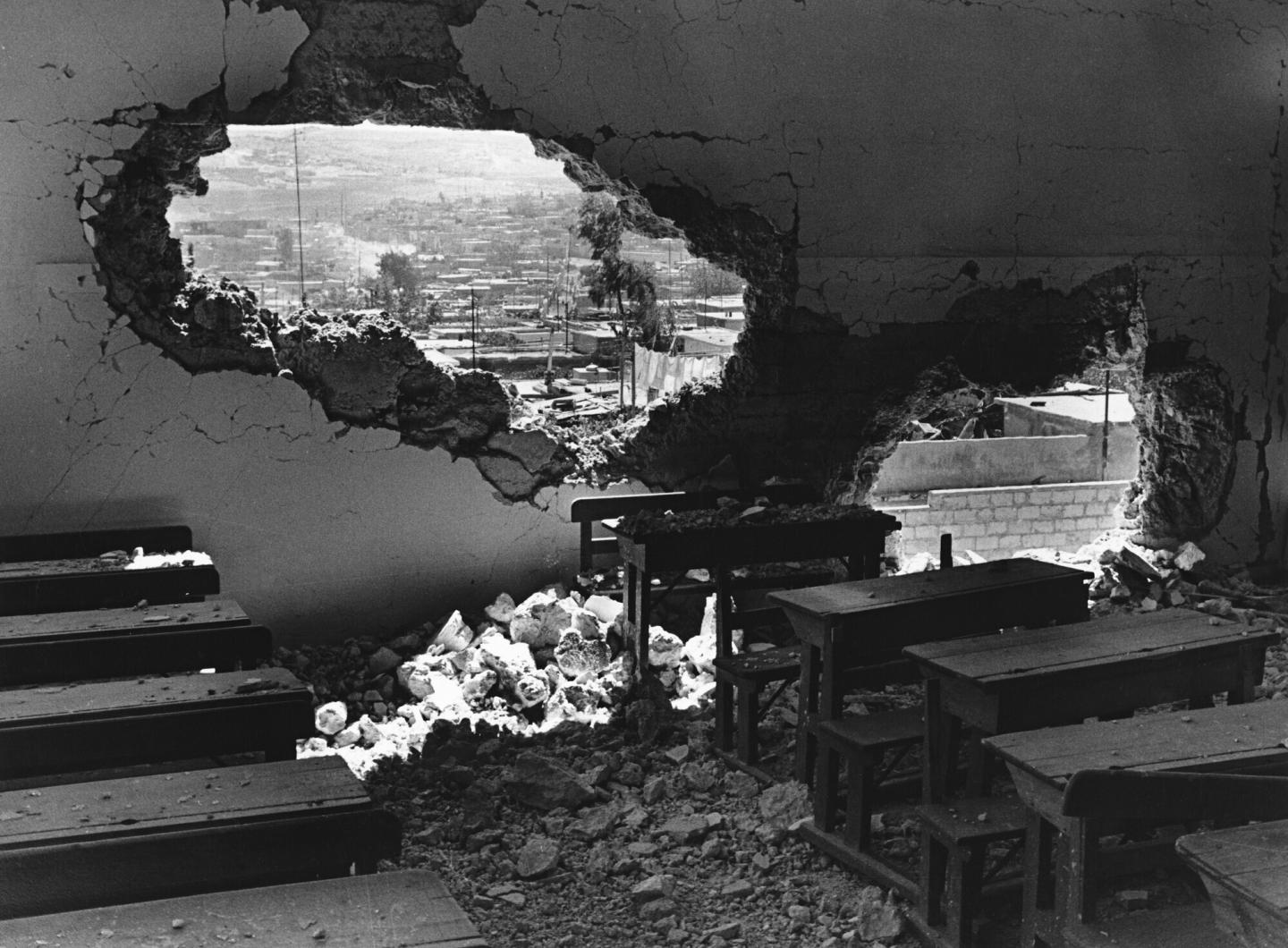

In June 1967, as the Six-Day War erupted in the Middle East, one of Sophie Farran’s first thoughts was the large amount of needlework stored in her Jericho home, ready for hemming and finishing. What if these handstitched products, nearly ready for sale in the U.S. or Canada, were destroyed?

A refugee who had fled to Jericho from Jerusalem in 1948, Sophie was hired by MCC in the early 1950s. Because of her English skills, she was asked to help the earliest MCC service workers acclimate to the region, but her work soon became broader.

Throughout the 1950s, she reached out to Palestinian refugees in Jericho and surrounding villages, inviting women to do embroidery work that could be sold abroad.

“The women were eager to work. This was the only way they could earn money to support their families,” she recalled.

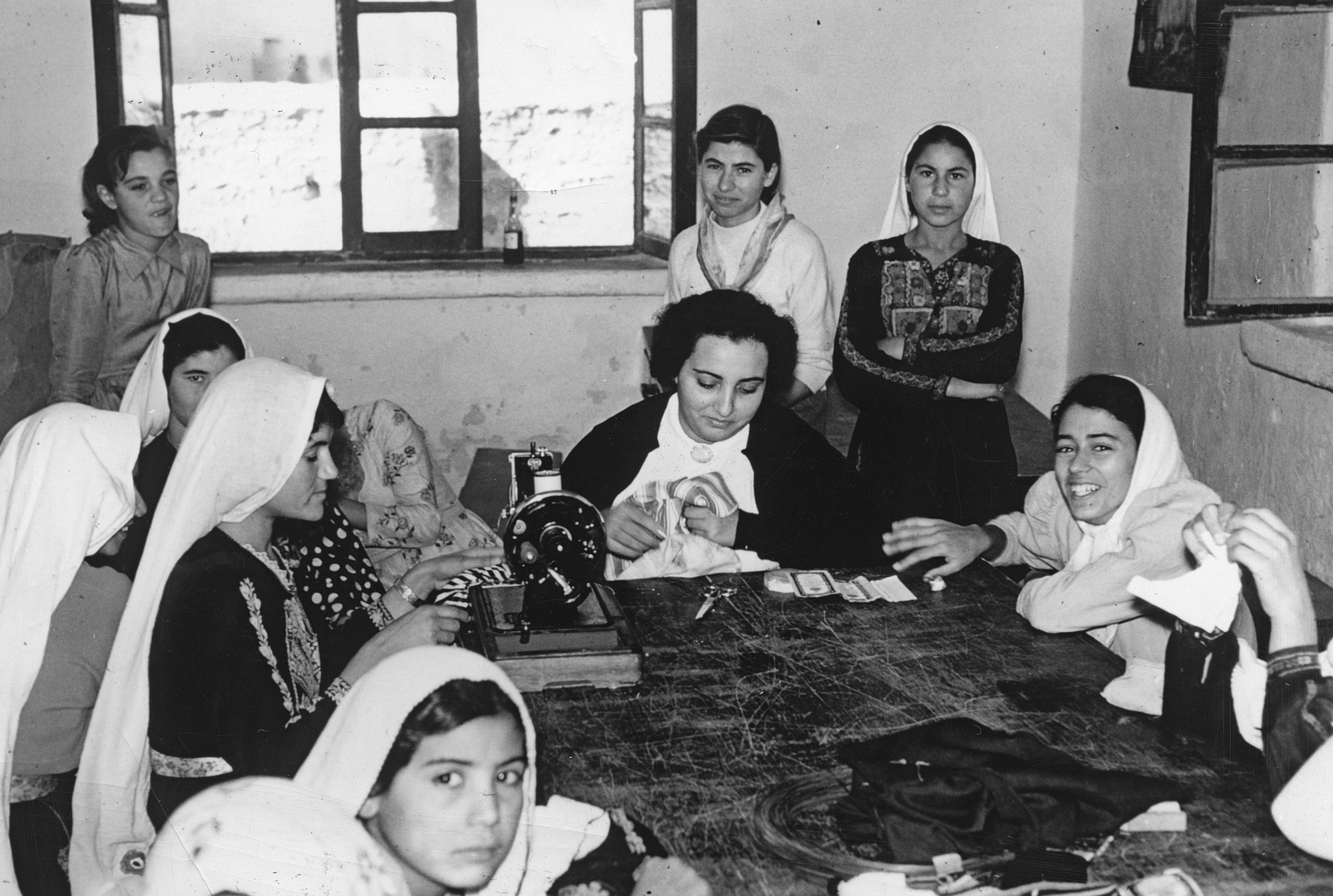

Her home in Jericho became a gathering place for women to do MCC-sponsored embroidery, and many nearly finished pieces were stored on site.

In 1967, though, with war spreading through the region, she felt accountable to MCC and the local women who depended on the income these pieces would bring. In the days that followed, Sophie passed out needlework to women in her neighborhood for finishing and safekeeping.

As fighting came closer, many fled. Those who remained waited in their homes for the shelling to cease. Women took up the work given out by Sophie to gather their scattered thoughts and fears during those tense days. The patterns that grew from their needles represented the order and structure for which they longed. The rhythmic flow of the craft soothed their nerves and relieved stress.

Months later Sophie discovered that those who had escaped to the neighboring country of Jordan did the same, taking their needlework along when they fled. When the roads reopened, the work was returned to Jericho with instructions to give it to Sophie.

An MCC visit to several refugee camps in Jordan later that year reaffirmed the value of this program. “In the first camp,” Sophie reported, “I found one of my needlework women teaching sewing.”

When I first arrived in the West Bank 13 years ago, I admired the needlework displayed in the markets and the Surif Cooperative, an MCC partner. Over time, I gained a deeper appreciation for the traditional skills and the culture of Palestinian embroidery, known as Al Tatreez al Falisteeni, and for the steadfastness and courage of the Palestinian women that made the needlework program possible through MCC.

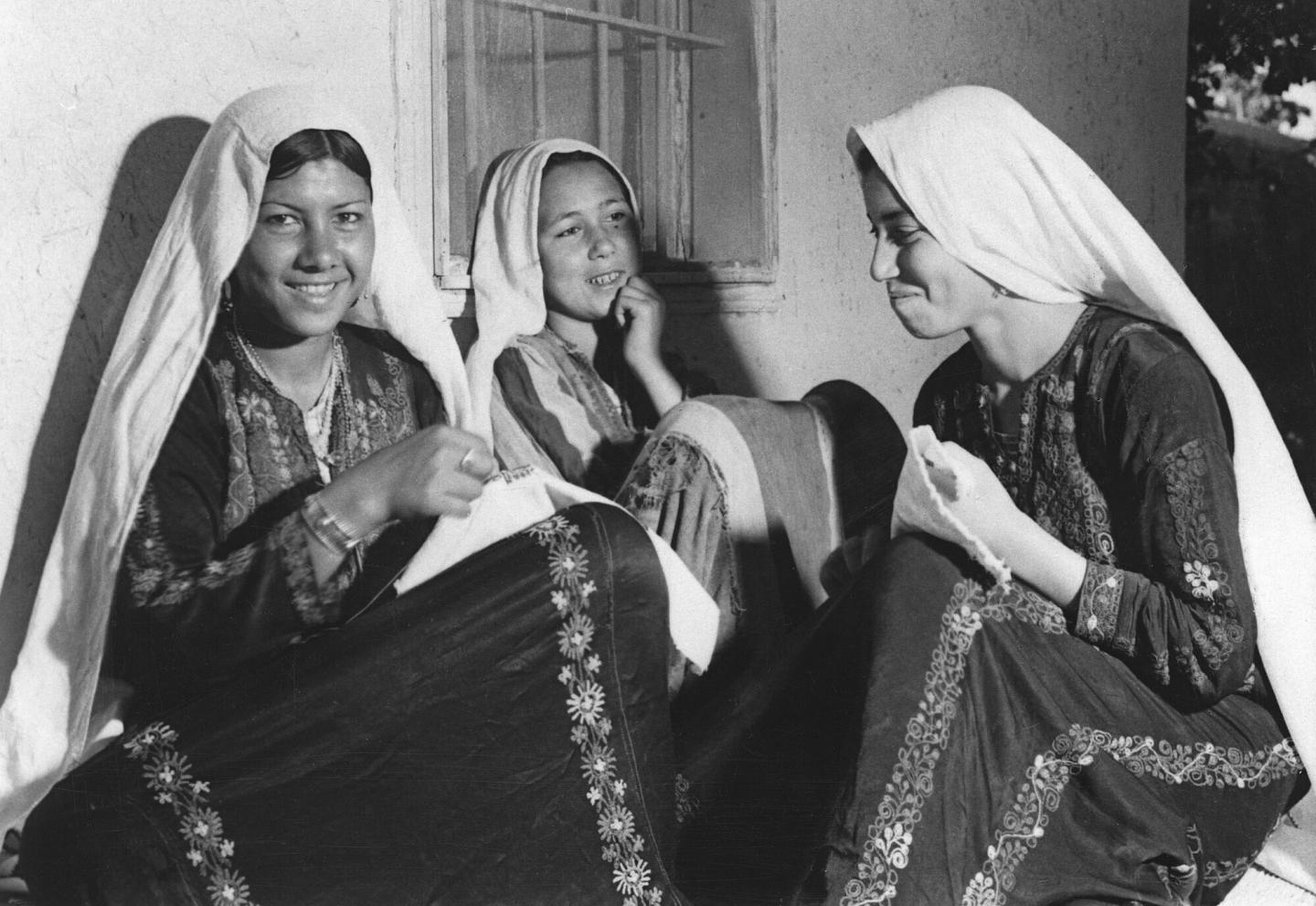

During the height of the Palestinian needlework tradition in the late 1800s and early 1900s, in the last years of the Ottoman Empire, young women learned the skill of embroidery and traditional patterns at an early age and spent years embroidering their long flowing dresses known as thobes with elaborate motifs that spoke of geography, status and significant milestones.

Skilled embroidery work was valuable and heirloom pieces were sometimes removed as panels and reattached to new garments or other household items. Brilliant silk threads and metallic cords spun visual tales on lavish textiles recounting the lives, families and communities of the women who wore them.

Like so many aspects of life in Palestine, war and displacement took its toll on this heritage craft. Eventually basic fabrics of cotton replaced silks and satins, and elaborate designs were simplified and standardized.

Over the years, I heard the stories of women who had been evicted from their homes and villages along with their families and forced to move from place to place to escape violence. I imagined their lives before displacement by their accounting of what was left behind: treasured photographs, favorite clothes, vibrant orchards and beloved books.

With little time, they packed only what they could wear or carry. Some women were able to take their heirloom needlework, others kept only the knowledge and skills of the art form.

In the refugee camps and in the villages, where there was always a shortage of food, water, medical supplies and other necessities, many women were forced to sell their most prized possessions to meet the needs of their families.

While MCC’s relief program established feeding stations and coordinated distributions of blankets and clothing, the needlework program was able to provide meaningful employment for hundreds of women trapped in the aftermath of the disaster.

And the needlework program improved women’s lives in ways that reached beyond family income.

Outbreaks of infectious disease in the camps prompted MCC to maintain a strict requirement that all women bring a certificate of health from a doctor before joining a needlework group.

“Since there were many cases of tuberculosis after the ’48 war,” recalled Sophie, “we required each woman to bring a certificate from a doctor showing that she was free of TB.”

Many women were reluctant to see a doctor for the very first time. This requirement prompted them to go and be tested for TB, helping to reduce the spread of disease among an already vulnerable population.

In the wake of trauma, war and loss, the needlework program helped to stave off isolation, which can be a strong predictor of negative mental health outcomes.

Through the MCC-sponsored embroidery groups, women were offered connection, comfort, routine, resources and practical assistance. The soft folds of cotton and the smooth slip of thread distributed through the program were sensory antidotes to the harsh realities of the environment of displacement.

The shared endeavor of filling holes with thread eased feelings of loneliness and isolation for grieving and weary women. When all seemed lost, working heritage motifs in basic form kept memories and identities alive.

Over the years, the supplies of thread and materials offered by MCC, the trainings and courses in business management and the marketing of the pieces in Canada and the U.S. helped this craft to thrive in Palestine and gain appreciation in other parts of the globe.

By 1976, when Sahir Dajani joined MCC as director of the needlework program, the goal was to grow Palestinian leadership. Sahir, with her parents and seven siblings, fled the violence in Palestine when she was a child, living in Lebanon, Jordan and Egypt before marrying and living in the U.S., then returning to Palestine.

Sahir worked to establish the Surif Needlework Cooperative and introduced the women to the idea of increasing Palestinian leadership with the goal of becoming self-sustaining. Not only was Sahir responsible for helping these women standardize production, she also taught management and accounting skills and methods for collective decision-making.

While I never had the opportunity to meet Sahir, I learned about the impact of her work during my visits to the cooperative some three decades later.

Each week, in the large main room surrounded by patterns, shelves full of finished products ready for shipment and several pieces in the making, women continue to gather to stitch distinctive designs reflective of the now blended heritage of the region. They meet to develop their own expertise, provide for their families and maintain hope, something that is constantly threatened in communities that have lived under decades of occupation by the Israeli military.

Through MCC, women from Palestine and around the globe have been drawn to this work.

In 1952, Ruth Lederach, an MCC worker serving as a nurse in Arroub, West Bank, proposed that MCC establish an embroidery project. Ada and Ida Stoltzfus, originally from Morgantown, Pennsylvania, navigated the winding dusty roads of the South Hebron Hills in their station wagon to connect women in that region during the early days of the program.

Edna Ruth Byler tirelessly promoted this forerunning fair trade craft among women’s groups in the U.S. and Canada. Many have come to appreciate the beauty of Palestinian needlework and celebrate it as just one of the many unique contributions of Palestinian people and culture to our world.

The MCC Palestinian needlework program demonstrates that as children of the Creator, we are at our best when we bond and beautify. Working together creates the kind of support needed to get through the worst of times. The desires to work with one’s hands and transform the plain or broken into something of meaning and beauty, to connect with our roots and identity, to celebrate interdependence, are all threads in the common fabric of humanity.

Heather Lehman and her husband Ryan served as representatives for MCC’s work in Palestine and Israel from 2007 to 2010. She’s now administrative assistant for MCC U.S. National Program.

Sources include:

"Palestinian Needlework and Costume – how a threatened national heritage has been preserved and how the skills and traditions of this heritage have helped to preserve the national identity of the Palestinians," by Aisha Elalami, https://aishaelalami.wordpress.com, Wordpress, 2018.

Salt & Sign: Mennonite Central Committee in Palestine, 1949-1999, by Alain Epp Weaver and Sonia K. Weaver, Mennonite Central Committee Canada, 1999.

We Sat Where They Sat: Ada and Ida Stoltzfus - Thirty-Seven and One-Half Years in the Ancient City of Hebron, by Marie E. Cutman, 1996.